DAZN, Serie A e streaming: dove stanno i problemi?

Immagino sentiate la mancanza dei miei articoli polemici, quindi eccone uno. Parliamo di DAZN, della Serie A, di streaming e dei problemi che qualcuno ha avuto nella visione delle prime partite di questa stagione: mi sono capitati sottomano in questi giorni articoli di “esperti” con idee molto poco chiare che parlano di banda larga, di codec, di reti, di capacità dei server e altro.

Non ci siamo.

Siccome esattamente come nel caso dei vaccini la disinformazione fa danni e porta in direzioni sbagliate, vi regalo le mie competenze (la progettazione di infrastrutture per eventi straordinari come questo costituisce gran parte del mio lavoro) per fare chiarezza: se siete giornalisti e questo articolo non vi basta, sentitevi liberi di contattarmi.

Fatemi iniziare con un pò di sano debunking e quindi dall’esplorare quali non sono le cause della bassa risoluzione / buffering / interruzioni:

- Non è la banda larga: il concetto di “banda larga” è riferito all’ultimo miglio, in sostanza alla connessione tra voi e la centrale Telecom più vicina. Per tutta una serie di ragioni che non vi sto a spiegare (questioni di fisica dei mezzi trasmissivi), questo è stato storicamente il collo di bottiglia delle reti. In alcune zone d’Italia si naviga a 1 gigabit al secondo, in altre a 250 megabit, in altre ancora a 30mbps e in alcune addirittura a soli 7mbps: quest’ultima è più che sufficiente a ricevere un flusso video con risoluzione decente, anche se la velocità effettiva dovesse essere inferiore. Non fraintendetemi, la lenta diffusione della banda larga può essere una serissima questione di sviluppo economico, ma in questo caso, semplicemente, non è il nostro problema.

- Non sono i codec: alcuni codec possono essere più pesanti di altri sulla CPU, ma a meno che non stiate usando un PC di 25 anni fa più o meno qualunque processore è in grado di mostrare uno streaming in qualità accettabile senza interruzioni. A meno che sul vostro computer non girino anche un miner Bitcoin e 327 virus con cui condividete la capacità di calcolo, ovviamente.

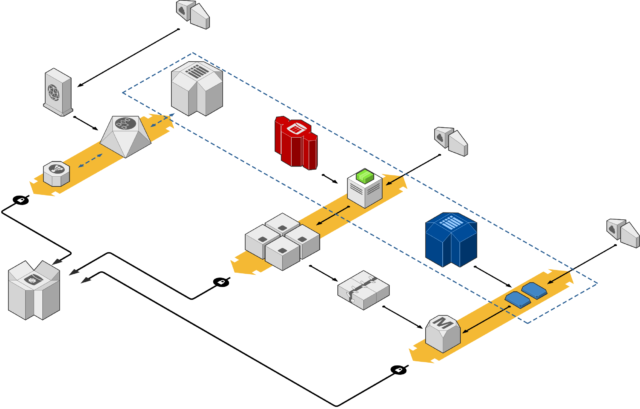

- Non è nemmeno la capacità dei server: la tecnologia si è evoluta e le realtà al passo con i tempi (e DAZN lo è) utilizzano infrastrutture elastiche, pronte a scalare per servire più richieste in pochi minuti, nel caso in cui si renda necessario. Di solito lavoriamo perchè le previsioni di carico siano adeguate, ma anche nel caso in cui si dimostrassero errate, correggere il dimensionamento sarebbe cosa da poco. Tutto questo, in una infrastruttura correttamente progettata, ad un costo molto basso.

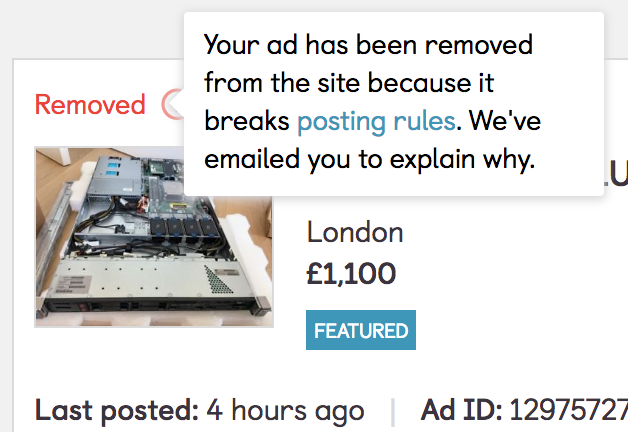

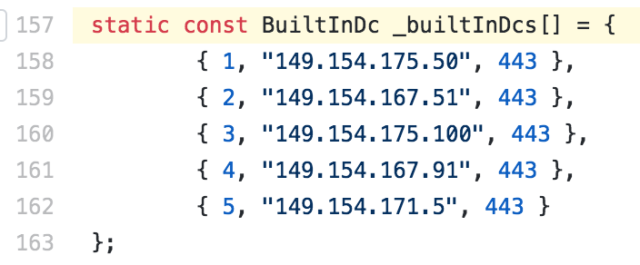

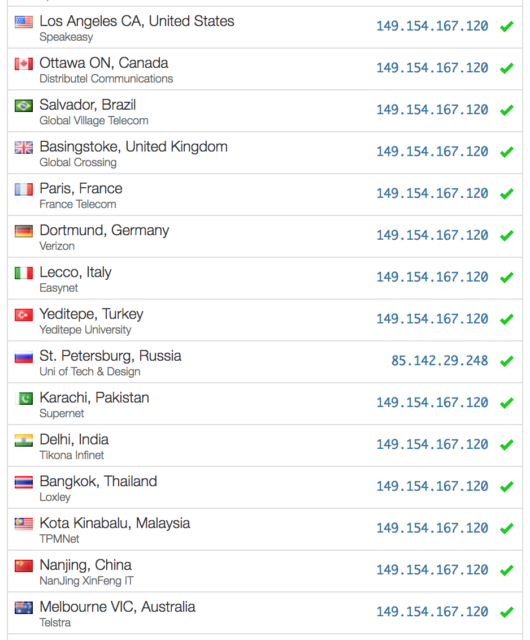

- Non è colpa della collocazione geografica delle CDN: questa è una teoria interessante ma totalmente campata in aria, e ci spenderò qualche minuto. Le CDN sono reti ad altissima capacità il cui compito è consegnare contenuti (video, immagini) agli utenti finali (voi). In rete si trova un comunicato stampa di DAZN in cui annunciano di aver scelto LimeLight, che in Italia ha infrastruttura a Milano e Palermo, come partner CDN: secondo gli scienziati, era ovvio che una CDN con presenza solo a Milano e Palermo non fosse all’altezza. Ma questo è sbagliato, per vari motivi:

- L’analogia “immaginate come sarebbe difficile fare la spesa se gli unici due centri commerciali in Italia fossero a Milano e Palermo: da Roma sono 600km, quasi 12 ore di macchina tra andata e ritorno” potrebbe sembrare sensata, ma è pretestuosa: per la spesa settimanale si impiega un’ora normalmente, il viaggio Roma-Milano aumenta questo tempo di 12 volte ed equivale alla perdita di una giornata intera. Per i dati che viaggiano su fibre ottiche invece è il contrario: le “operazioni intermedie” indipendenti dalla distanza impiegano comunque qualche millisecondo, ed il dover percorrere una tratta di 600km al posto di una lunga solo 6 cambia di pochissimo il ritardo totale.

- Se invece che usare Google in cerca di comunicati stampa i sopracitati scienziati avessero analizzato lo streaming vero, si sarebbero accorti che DAZN usa almeno tre CDN diverse, alcune con presenza più capillare in Italia. La storia di Palermo e Milano quindi non regge, o comunque non può essere banalizzata su un fattore di semplice distanza.

- Internet non soffre di barriere nazionali (non ancora perlomeno), e le CDN hanno altre presenze vicino all’Italia come Vienna, Zurigo, Marsiglia, Monaco etc: è realistico pensare che anche queste location contribuiscano all’esperienza del pubblico italiano.

Arrivati a questo punto vi starete chiedendo dove stia il problema, ed eccoci alla risposta: non lo so, ma ho un paio di “maggiori indiziati”, che vi espongo.

Il primo è la particolare conformazione della rete italiana che per questioni geografiche e soprattutto storiche consiste di fatto in una stella con centro a Milano. Le interconnessioni tra diversi provider (tra le quali, ad esempio, la connessione tra chi vi vende la linea internet di casa e la CDN di DAZN) avvengono quasi esclusivamente lì, rendendo di fatto inutile la localizzazione geografica dei punti di distribuzione contenuti (per farla molto semplice, anche se la CDN di riferimento installasse un nodo nella vostra stessa città, con buone possibilità si dovrebbe comunque passare da Milano, o quantomeno da Roma, per raggiungerla).

Questo ci porta al secondo fattore in gioco: il trasporto dati nazionale di lunga distanza (il collegamento Napoli-Roma-Milano, per intenderci) ha costi relativamente alti se comparato a tratte molto più estese (Londra-New York), dettati dalla complessità infrastrutturale e dalla scarsità di competizione e di investimenti. Il traffico in rete è esploso negli ultimi anni, e certe tratte di interesse internazionale si sono sviluppate in modo molto veloce e spinto – altre, di interesse meramente nazionale, sono rimaste indietro e si stanno muovendo più lentamente. In questa condizione è facile che per motivi tecnico-economici si creino situazioni di congestione temporanea durante eventi eccezionali, per il semplice motivo che evitarla sarebbe troppo costoso.

Il terzo fattore è relativo al criterio di dimensionamento dei trasporti digitali, che spesso si deve per forza basare su dei dati di utilizzo medio. Torniamo all’analogia con i trasporti automobilistici: nelle due settimane centrali di Agosto sarebbe indubbiamente comodo se tutte le autostrade a tre corsie ne avessero invece cinque. Perchè allora non ne hanno cinque? Per il semplice motivo che quelle corsie sarebbero da mantenere tutto l’anno pur essendo necessarie per sole due settimane: i costi, in altre parole, avrebbero la prevalenza sui benefici. Lo stesso accade su certe tratte di trasporto difficili da ampliare e mantenere (molte altre sono invece dimensionate in base al picco di traffico atteso, quindi sulla base del caso peggiore).

Non si può infine non citare il nostro buon vecchio PEBKAC – acronimo che in informatica si usa per indicare il problema che sta tra la sedia e la tastiera (in questo caso tra la poltrona e il telecomando), cioè l’utente. In molti si sono avvicinati ai servizi di streaming per la prima volta in questa occasione, e non hanno mai verificato prima che la loro rete di casa (banalmente, il Wi-Fi) fosse pronto a gestire un simile traffico. Sono pronto a scommettere che gran parte dei problemi stia qui.

Tutto chiaro ora? Se ci sono domande chiedete pure.