Eventi straordinari e siti istituzionali: un rapporto (ancora) tormentato.

Anni fa ho scritto questo articolo (in un momento di frustrazione causata dalla puntuale indisponibilità dei siti istituzionali nei momenti di loro maggiore utilità), nella speranza quantomeno di aprire una linea di dialogo. Ero stato fortunato e questa si era aperta, ma il tutto era stato impacchettato e rispedito al mittente senza troppi complimenti.

Il problema in breve: sono molti i siti informativi, soprattutto in ambito Pubblica Amministrazione, “inutili” e poco visitati per il 99.9% del tempo, che però diventano critici in momenti di particolare interesse. Immaginate ad esempio il censimento della popolazione: ha cadenza decennale e dura due mesi. Durante questa finestra di tempo ogni cittadino userà l’apposito servizio online, ovviamente aspettandosi che tutto funzioni a dovere.

Altro esempio è il portale del Ministero dell’Istruzione: basso carico per gran parte dell’anno, ma quando vengono annunciate le commissioni di maturità, deve essere funzionante, pronto e scattante. Pensate poi al sito dove vengono pubblicati i risultati delle elezioni: utilizzato ogni quattro o cinque anni, diventa il più visitato d’Italia durante le poche ore di scrutinio.

Internet oggi è la fonte primaria di informazione per molte persone: è un dato di fatto che non si può ignorare, ed è necessario dare adeguata importanza alle piattaforme che contribuiscono a questa informazione.

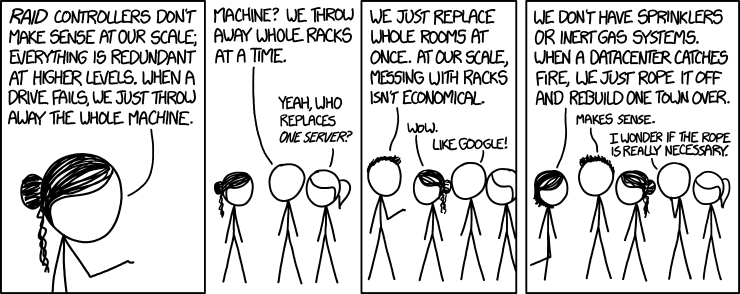

Ne parlavo nel 2011, perchè è stato l’anno in cui i tre servizi sopracitati hanno mancato il loro obiettivo primario: quando servivano, non funzionavano. Se ne era parlato, soprattutto tra gli addetti ai lavori: ci eravamo arrabbiati, ma qualcuno aveva commentato che le soluzioni al problema (che spaziano da questioni molto tecniche come lo sharding dei database e l’elasticità delle infrastrutture a questioni più di buon senso, come una corretta previsione dei carichi) erano molto distanti dal mondo dei “comuni mortali”, e ancor di più dal settore pubblico.

Un punto di vista secondo me contestabile, ma quasi sicuramente con un fondo di verità: al tempo il concetto di “cloud” esisteva da pochi anni, e alcuni vendor dubitavano ancora delle sue potenzialità.

Sembra di parlare della preistoria.

(per non dimenticare: il load balancing manuale delle Elezioni 2011)

(per non dimenticare: il load balancing manuale delle Elezioni 2011)

Adesso siamo nel 2017: sono passati sei anni dal mio articolo e come alcuni continuano a ripetere, “cloud is the new normal”. Il cloud è la nuova normalità, tutti lo usano, lo scetticismo, se mai c’è stato, è sparito: il tempo ha ormai provato che è una nuova e rivoluzionaria tecnologia e non solo un trend temporaneo o una pazzia di un singolo vendor.

In questi anni, nella nostra PA, sarà cambiato qualcosa?

Alcuni segnali fanno ben sperare: Eligendo ad esempio, il portale delle Elezioni, è esposto tramite una CDN (ma non supporta HTTPS). Altri fanno invece perdere la speranza appena guadagnata: questo mese si è tenuto il Referendum per l’Autonomia della Lombardia – serve che vi dica in che stato era il sito ufficiale durante gli scrutini? Timeout.

Le soluzioni a questo tipo di problemi sono ormai ben conosciute e consolidate: caching estremo, utilizzo di CDN, sfruttamento di infrastrutture scalabili, etc. I costi sono molto bassi e granulari: con una architettura ben studiata, si possono servire tutte le richieste senza sprecare un euro. Fa in un certo senso pensare il fatto che in certi ambienti siano ancora presenti e gravi problemi che l’industria ha risolto già da tempo, come quello dei picchi di carico.

Quali sono quindi i fattori limitanti, quindi?

Non stento a credere ci sia una scarsa comprensione del tema e della sua importanza ai “piani alti” di ogni ente: solo di recente siamo riusciti a mettere insieme una community di sviluppatori e un “team digitale” (composto da professionisti di veramente alto rango) volto a svecchiare il “sistema Italia”.

L’iniziativa sta già portando i suoi primi frutti, ma si tratta di un team per ora piccolo molto focalizzato sullo sviluppo e non sulle operations/mantenimento: il passo per il cambiamento della mentalità generale è ancora lungo. Non è difficile immaginare come una scarsa comprensione del tema porti molto velocemente alla mancanza di interesse e di risorse dedicate – con conseguente frustrazione di quelli che sono i “piani inferiori”.

Un secondo fattore spesso portato (o meglio, trascinato) in gioco è la scarsità di infrastrutture: se questo poteva essere vero una volta, oggi, con l’affermazione delle tecnologie cloud e del concetto di “on demand”, questo smette di essere un punto bloccante. Le infrastrutture ci sono, basta sfruttarle.

Ultimo, ma non per importanza, il discorso “competenze”: non stento a credere come molti fanno notare che sia difficile reclutare personale adatto e che chi si occupa oggi di sistemi nella PA abbia ben altre responsabilità e quindi ben altre basi. Ritengo però non si possa ignorare il fatto che al giorno d’oggi il concetto di “as a service” (servizi managed se volete chiamarli con un nome forse più familiare) rimuova buona parte di questo problema, e che l’immensa offerta di training e relativa facilità di sperimentazione renda estremamente facile la coltivazione delle skills mancanti.

Può servire tempo, ma da qualche parte bisognerà pur partire. Molti IT manager e sistemisti sono lì fuori pronti, a fare il passo: hanno solo bisogno di essere ispirati.

Ispiriamoli, no?