Me and HP: a “bare-metal” odyssey

If you follow me on social media you’ve almost certainly heard of the issues I’m facing with the HP DL320 Gen8 I bought a few months back to replace my NAS and some test machines.

In term of diagnosing and solving this problem HP’s tech support has been useless so far, so in the last few weeks I’ve been digging deeper and deeper into this, and here are my findings (in logical, and not chronological, order).

Let’s start from scratch, for the benefit of who has not been following this from the very beginning: I’ve installed, tested and shipped the machine with the main drives only (Samsung 850 EVO SSD), as the capacity ones I wanted to use (SATA 2.5″, 1TB, 7200rpm) turned out not being easy to find on the market.

When I was finally able to buy 2+1 drives of the exact HGST model I was after, I screwed them to their caddies and shipped them to the colocation: when they confirmed the drives had been placed into the server, I rebooted it and configured them in a mirrored mdraid array.

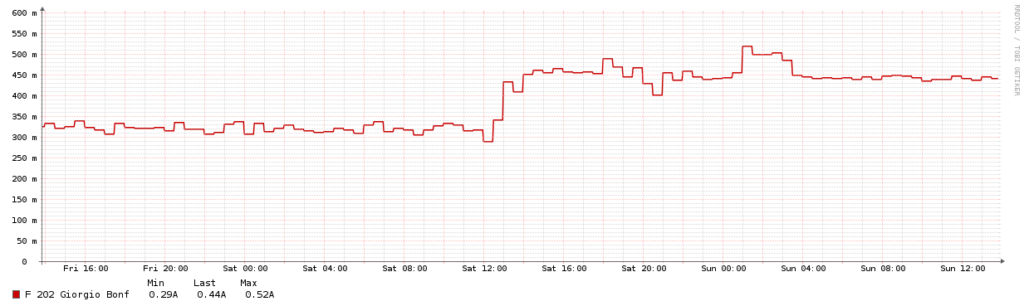

Then I noticed that power consumption had gone up from 0.3 to 0.5 Amps:

The raid (re)build was still ongoing and CPU usage was high, so I just ignored this, even if even during previous spikes I had never seen such an high power consumption. To mi surprise, the morning after power usage was still 0.5A, even if the rebuild had finished hours before and load average was back to 0.0something.

With no evidence of something being wrong with the system itself, I blamed the drives (HGST HTS721010A9E630) and started researching for someone else facing the same issue with them. Nothing came out, as expected, and got confirmation from some docs that the power usage to be expected was way lower than what I was seeing.

By chance, I found some threads on the HP forums mentioning situations where non-genuine hard drives were causing “high noise”. Being unable to check the noise by myself without travelling to the colocation, I went ahead and had a look at the fans speed in my iLO, to realise all of them were running at 100%: at that stage I didn’t knew the pre-upgrade reading (now I do: 19%), but while testing it at home (in a way less controlled and warmer environment than the datacenter) I had never seen anything above 30%.

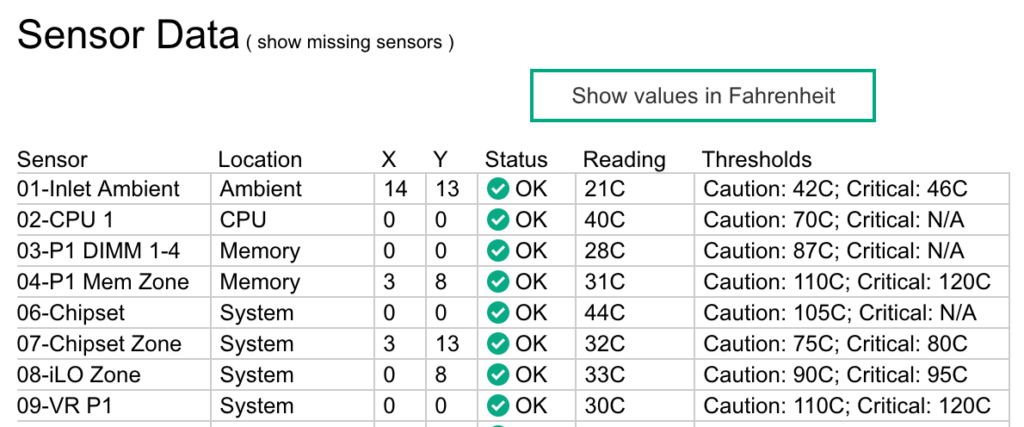

At this stage, I had finally found the cause for that huge power usage: extremely high fan speed. It was now time to try and explain the latter. First thing I checked, of course, were temperatures around the system: everything was good according to the iLO, no alarms nor criticals (not even warnings) and SMART readings were fine, with 20/21C on every drive. Nothing was explaining why the DL320 was trying so hard to cool itself down.

Then I found this article, where David described the same problem and found the perfect name for this phenomenon: Thermal Runway. Based on his description, looks like I’ve been very lucky, as other HP ProLiant servers are even shutting themselves down due to wrong temperature readings. Needless to say, my hard drives P/N were in its list of known bad ones.

Scraping the IPMI details, I found the sensor who was causing this whole thing: “05-HD Max”, which was at 58C. I’ve researched its details, and looks like it’s not a physical sensor, but rather an average of all of the SMART readings. With the temps for my four drives being around 22/23C max according to SMART, there was no way their average could have been 58C. Making things worse, this sensor has an hardcoded, non editable warning threshold at 60C.

With no clue on what to do next, I tried asking HGST if there was a firmware upgrade available (the DL320 G8 is on latest version of everything), but after 15 days, a number of emails and multiple levels of escalation they didn’t even manage to understand what I was asking for, so I decided to give up with them.

At this stage, with all the details I was able to gather I logged a support case to HP, and at the same time bought two new Seagate HDDs (ST500LM021-1KJ15), just to learn, after trying them, that they cause the same problem.

After a very honest first answer where HP’s tech support told me that the system was speeding up FANs as the drives were not recognised as HP genuine, they changed their mind and started pretending the 58C reading was real, and my drives were really running so hot.

I was lost again, and started wondering what did prehistoric people do before the cloud came, when they had this kind of hardware issues. Their first step was probably to go in front of the broken server, so I jumped on a plane and did the same.

(a picture of MY-ZA while undergoing surgery)

First thing, I was able to confirm the 58C reading was definitely wrong (as expected, anyway, but I was looking for a proof to show HP), and SMART was right: drives were super-cold, even if extracted while running. Moreover that sensor was jumping from 24C to 58C in 2/3 seconds after placing them in, which is rather hard (just think about the thermal shock).

Second, I tried to put the drives in different positions (and on a different port of the P420i RAID controller), and the issue was still there.

As last resort, I connected them to the onboard B120i HBA, and the system started working properly. Sensor 05 back to normal, drives running ok, etc. Not a good solution tough, as I’ve paid for the P420i + cache and under no circumstance I will do without it.

Fortunately, while upgrading my iLO4 to firmware 2.55, I noticed that after resetting it sensor 05 was temporarily disappearing, until the next operating system reboot. With this sensor disappearing, everything goes back to normal: fans to 30%, consumption to 0.3A, my bank account not at risk anymore.

sensor 05 has disappeared: 03, 04, … 06.

So, even if not particularly good looking and clean, I had found a solution: resetting the iLO. I went ahead and installed freeipmi, then made sure “bmc-device –cold-reset” is run 30 seconds after the system boots.

I’m still holding some kind of hope in HP support: I asked them to provide me with a way to permanently disable that sensor or raise its threshold, at my risk (read: voiding warranty).

It’s hard to describe how frustrated I am with both with HP servers, policies and support: not being able to test all existing parts and so having some “genuine” and some non genuine ones is okay, but artificially messing up a temperature reading to increase power consumption (and thus costs) and force their customers not using parts from 3rd parties can only be defined with a word: sabotage.

Giorgio